Common Mistakes

There are a few common mistakes and not-very-obvious expectations about how to handle things that we've seen while helping new Denizen users. To help you master Denizen more quickly, we've listed a few of these issues and what to do about them below.

Display Text vs. Data

An important distinction to learn is the difference between display text and real data.

Real Data is actual internal data, formatted for your scripts to process as easily as possible.

Display Text is some message you display for users to see, often generated using real data.

As a general principle, real data can be used to generate display text, but display text should never be used to generate real data.

The following are some examples of ways users have been seen mixing up real data and display text.

Item Lore Is Not Data

One common mixup between real data and display text is item lore.

It's natural to think "well, my item has a lore line that says Bonus Damage: +15, so I need to get that +15 from the lore during the damage event to actually apply it!" This, however, is working backwards: that would be converting display text to data, when you should only ever convert data to display text, never the reverse.

Custom real data for an item can be stored in a few different places:

Item flags (accessed like

<[item].flag[flagname]>)Item script keys (accessed like

<[item].script.data_key[keyname]>)Vanilla minecraft features like the Attributes system

After you store the data in the proper place, you can then display that data in the lore. From there, always write tags/etc. based on the real data you stored, not the lore - that's for the human players to read, not your scripts!

Players Are Not Their Names

Historically in Minecraft, players were unique based on their name. This meant that "Steve" was theoretically always going to be "Steve". There was one true "Steve", nobody else could be "Steve" and "Steve" could never take on another name. This changed around the era of Minecraft 1.7, when UUIDs became the unique identifier of a player, and players were from there on allowed to change their names.

Never track a player's name internally. The <player.name> tag should exclusively be used for outputting a clean name in a narrate command or similar output meant to be read by players. As that's all a name is meant for: human reading. It is not meant for any internal tracking. It is not unique nor reliable.

* Note that there is one exception to this: the execute command runs external plugin commands, which will likely expect either a name or UUID as input, not a Denizen object.

So, A Player Is Their UUID?

A player is not just their UUID. A player isn't a name, a UUID, a location, or anything else. A player is a player.

Similarly, an NPC is not just their ID. An NPC is an NPC.

In fact, nothing is just that little piece of information that uniquely identifies it.

The Object System

An important part of the way Denizen functions is the object system.

An "object" in the world of software is a representation of something specific that can be tracked by a lookup identifier, that exists as more than just that lookup data. That's a bit confusing, so what does that mean in real usage? That means an "entity object" is a real full entity, with its AI and its health and its name and its specific place in the world and everything else that makes it what it is. The entity can be quickly looked up if you use the UUID, but the true entity itself is so much more than just a short set of numbers and letters. (Note for the curious: in most software programming languages, the unique identifier of an object is its memory address).

In Denizen, whenever you look at an object in debug or with a narrate command (or wherever else in text), the unique identifier is visible, with a prefix identifying what type of object it is (that's called Object Notation). This is not meant to be the object itself, but rather a lookup identifier so you or the system can read it and figure out what object was being referred to.

It's important when writing scripts to make sure you work with the actual object and not with some text that contains the lookup identifier.

A few examples of where this might come into play:

A player object is placed into a line of text. Say for example

"Player:<player>"is stored somewhere. When you read that text out, you may assume that<[THAT_TEXT].after[:]>is going to return the player object - but it won't. It will return plain text of the unique player identifier. You would have to convert it into a player object again, using either<player[<[THAT_TEXT].after[:]>]>or<[THAT_TEXT].after[:].as[player]>(though in some contexts, Denizen may automatically fix this for you).In some cases, reading directly from data storage (YAML, Flags, SQL, etc.) might return the plain text identifier of whatever object was inserted into it. When this happens, you again have to convert it back into the real object using the relevant conversion tags.

Generally when user input is given (in for example a command script). A unique identifier or even a non-unique one may be used, and you will have to do more complex real-object-finding. As a particular example of this, when a command script has a player input option, generally you can trust that users aren't going to type out the exact perfect object identifier. The tag

server.match_playeris useful for converting the human-input player name into a real player object.

Don't Trust Players

When you're writing scripts, you can generally assume that the system is going to process what you wrote as you wrote it. If you used a flag command to set a flag on a linked player, you can pretty safely trust that player.flag will then return the value of that flag.

Players, however, are not machines. They're human. Humans make mistakes - humans also sometimes like to cheat. When scripting user-input, you must prepare for and account for this.

Let's demonstrate the difference between a bad script that trusts players, and a good script that doesn't, using a "pay" command that you might have with an economy system.

pay_command:

type: command

name: pay

usage: /pay [player] [amount]

description: Pays the specified player.

script:

- money take quantity:<context.args.get[2]>

- money give players:<server.match_player[<context.args.get[1]>]> quantity:<context.args.get[2]>

- narrate "<blue>You paid <gold><server.match_player[<context.args.get[1]>].name> <green>$<context.args.get[2]>"

That script is nice and simple. Only takes 3 lines, and does everything it needs to do... if the player using it uses it exactly as specified without any mistakes or intent to abuse the system.

Let's see what that script looks like if we validate all user input with care. Read the comments in the script to see what was being prevented.

pay_command:

type: command

name: pay

usage: /pay [player] [amount]

description: Pays the specified player.

# Users might be jailed or similar and have their permissions taken away,

# so let's be sure to require a permission to use the command.

permission: myscript.pay

script:

# Players might just type "/pay" without remembering the input arguments,

# so if they do, just tell them what the input is and stop there.

- if <context.args.size> < 2:

- narrate "<red>/pay [player] [amount]"

- stop

# Use a fallback in case the player name given is invalid.

- define target <server.match_player[<context.args.get[1]>].if_null[null]>

# A user might mess up typing a player name.

# If there's no matched player, just tell them and stop there.

- if <[target]> == null:

- narrate "<red>Unknown player '<yellow><context.args.get[1]><red>'."

- stop

- define amount <context.args.get[2]>

# A user might mess up typing the number.

# If they did mess up, tell them that and stop there.

- if !<[amount].is_decimal>:

- narrate "<red>Invalid amount input (not a number)."

- stop

# A user might try to cheat by paying a negative value

# (so that they receive money instead of lose it).

# So, validate that the number is positive.

# Also exclude zero at the same time as there's no reason to pay $0.

- if <[amount]> <= 0:

- narrate "<red>Amount must be more than zero."

- stop

# A user might try to pay more than they have, either as a cheat or by accident.

# Make sure they can afford it and stop if they can't.

- if <player.money> < <[amount]>:

- narrate "<red>You do not have <green>$<[amount]><red>."

- stop

- money take quantity:<[amount]>

- money give players:<[target]> quantity:<[amount]>

- narrate "<blue>You paid <gold><[target].name> <green>$<[amount]>"

That's an awful lot of things that needed checking! Unfortunately, good user-input scripts tend to get pretty long from all the input validation that's needed. Luckily, nobody should be able to break these longer scripts!

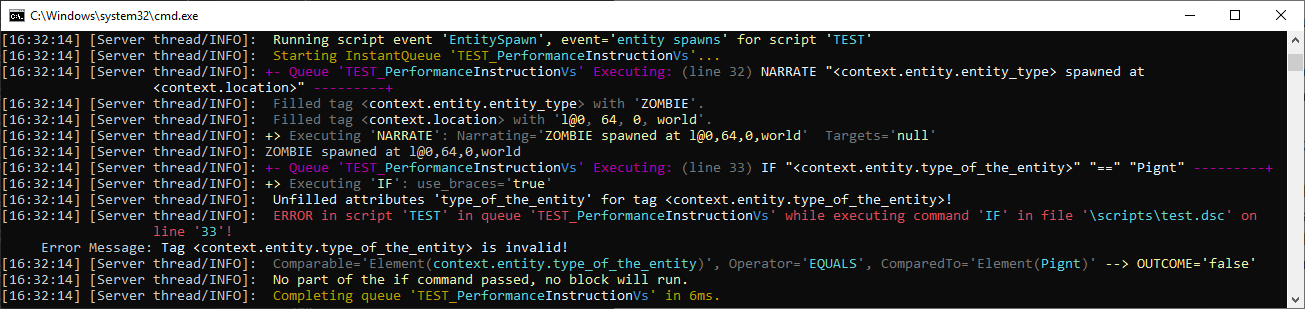

Don't Compare Raw Objects

Raw object comparison is one that seems at first natural to do, and you don't realize the problems until they bite you much later on.

"Raw object comparison" refers to use an if command or similar to compare a raw Denizen object to something else (often plain text of the object identity).

This looks, for example, like this:

- if <player.item_in_hand> == i@diamond_sword:

- narrate "You have a diamond sword!"

At first glance, this looks mostly fine. If you test it in-game, it will probably even work. So what's the problem?!

Not Always Just A Sword

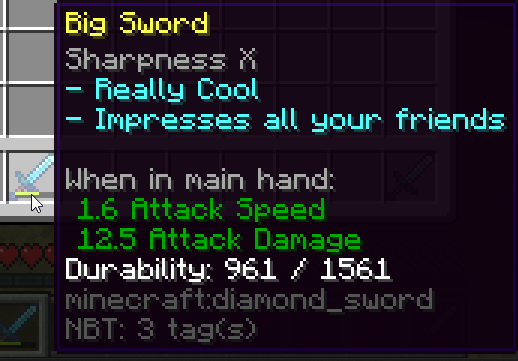

The first problem with this is that non-unique objects in Denizen (those that are identified by their details, like an item is, as opposed to objects that identify by some ID, like entities do), often include secondary details in specific circumstances, even if they didn't in your early testing.

The if command in the example above will stop working the moment a player uses their sword a bit, as the durability value will change and now they'll have i@diamond_sword[durability=1]. This will also change if they enchant the sword, or rename it at an anvil, or...

Identifier Style Changes In Denizen

The second problem with this is that what's valid now might not be valid in the future. Denizen changes often, and the way objects identify change between versions. For example, <player> used to return p@name, but now returns p@uuid. Many other changes to identify format have happened over the years.

For the example given above, a sword that today is i@diamond_sword, might someday be i@diamond_sword[durability=0] or item@diamond_sword or i@item[material=diamond_sword] or diamond_sword[future_minecraft_shininess_statistic=0] or any number of other possibilities.

So What Do I Do?

Option one: where possible, use a dedicated matcher tool. The object type ItemTag defines a matchable of the material name, so you can use it with the matches operator:

- if <player.item_in_hand> matches diamond_sword:

- narrate "You have a diamond sword!"

Option two: compare objects based on reasonably-guaranteed-format tags. That is: tags that return a plaintext element of a clearly specified format, not an object.

The tag .material.name is guaranteed to always return just the material name, so the below comparison is safe from any item-detail-changes or future Denizen changes.

- if <player.item_in_hand.material.name> == diamond_sword:

- narrate "You have a diamond sword!"

With either of these options, the only risk is that the name of the material might change in a future Minecraft version (this would be harder to avoid - luckily, this happens very rarely and usually you'll know it's coming when it does. If you really want to protect against it, you could do == <item[diamond_sword].material.name>: to rely on the autoconversion that would be added in Denizen when a rename happens, but you don't really need to).

For other object types, find the relevant unique comparison point. For materials, worlds, scripts, plugins, ... you can use .name.

For notable object types (locations, cuboids, ellipsoids, ...), you should never compare them directly. Instead, note the object and check .note_name - or use more specific syntaxes, like the in:<area> switch on events.

Note On Exact-Same Objects

When you want to compare exactly-the-same-object (usually for unique objects like entities, or in list-handling tags, or similar), and you have a tag for both (instead of typing one as plaintext), you can be relatively safe doing direct comparisons.

For example, you might add - if <[target]> == <player>: to the /pay command example to prevent players trying to pay themselves. This would be acceptable, as the two values do literally refer to exactly the same object in theory, and thus they will not have any different details, and any identifier changes will automatically apply to both, not only one.

Note, however, that a stored copy of the object (such as a player object stored in a flag) could potentially in some cases retain an outdated format later on, thus breaking comparisons. Exact-Same object comparison is only safe when both objects are grabbed from a valid source tag.

Don't Overuse Fallbacks

Fallbacks are an incredibly handy tool in Denizen. They're one of the primary tools you can use to handle uncertain situations edge-cases in your scripts. They are, like most things, best in moderation. Excessive use of fallbacks can cause more harm than good.

Errors Are Scary

The mindset that tends to lead to fallback overuse is one where errors are scary. An error is a problem, so you have to get rid of errors by any means necessary!

In reality, errors are just another tool that Denizen provides. The error message itself is not the problem, the error is merely there to tell you that there is a problem somewhere in your script. If you put a fallback on every tag, you'll end up hiding errors without fixing the actual problem. Your script won't show any scary red text in the console, but it also won't do what it's supposed to be doing!

When To Use Fallbacks

A fallback should only be placed onto a tag when you're expecting that tag to fail.

Consider for example the server.match_player tag, which is used to convert user-input names into a player object. You can quite reasonably expect that sometimes a player will input something that isn't a valid player name, and the tag will fail. That's a case where you should absolutely add a fallback like .if_null[null] or the older style ||null.

When you add a fallback, you often will also need to check for the fallback value, like for a definition defined as <server.match_player[<input>].if_null[null]>, you might do - if <[target]> == null: and inside that block handle the case of an invalid player input. In some cases, where you only need the check and don't to use the value after, you can simply use .exists, like - if <player.item_in_hand.script.exists>: (to check if the player's held item is a scripted item at all).

In other situations, the fallback can simply be a reasonable default value, like <player.flag[coins].if_null[0]>, which you won't need to specifically account for with any extra if commands.

When To Not Use Fallbacks

Fallbacks should not be used when the tag doesn't have a very good reason it might fail.

For example, the tag <player.name> should probably not have a fallback in most scripts (unless it's a reusable script that doesn't specifically require a player to work).

If a script that uses <player.name> runs, and there isn't a player available, it will show an error message. This is good! This lets you know that something went wrong, and the script was ran without a player, which means you can from there look into why there was no player, and fix whatever caused it.

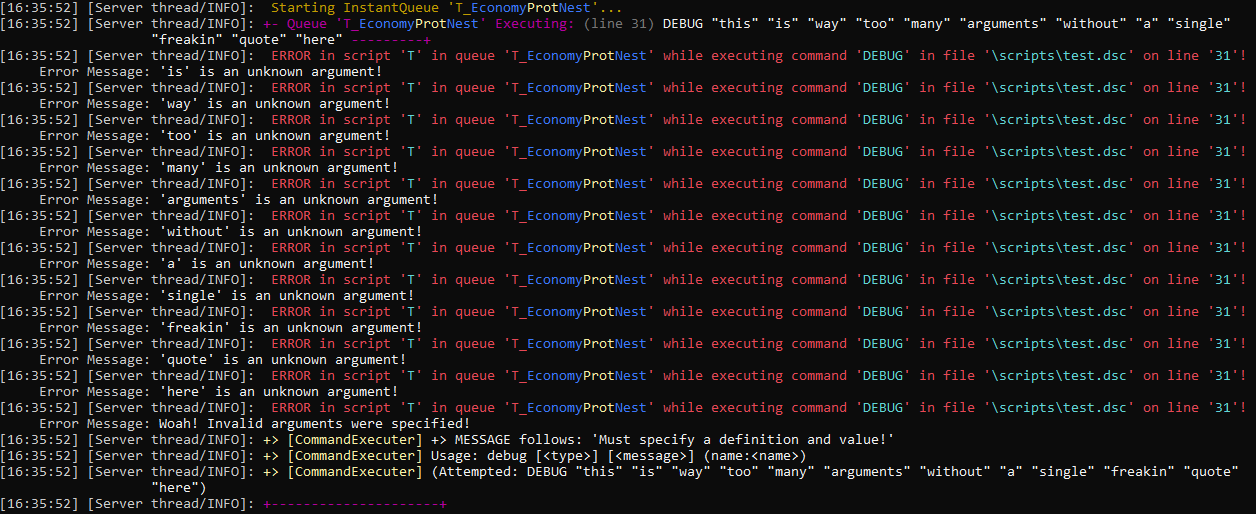

"Quotes Go Around The Whole Argument"

Many users tend to misunderstand where quotes go in Denizen commands.

Denizen syntax is structured such that a line starting with - indicates that that line is a command line. A command line is then made up of the command name and the command arguments. The command name goes first, then each argument is added, separated by spaces (and not by anything other than spaces). So, for example, - commandname arg1 arg2 arg3 is a line containing a command with three arguments.

When you need to use a space within an argument, you must put quotes around whole the argument, to indicate that it is a single argument. For example, - narrate "this is one big argument" is a narrate command with only one argument.

As another example, - flag player "my_flag:my value". This is a flag command with two arguments: player, and "my_flag:my value". Notice that my value is not a separate argument from my_flag. The colon (:) symbol is not a symbol that separates arguments, it instead merely indicates a prefix to an argument (which is still part of that argument!).

It is NEVER correct to put quotes inside an argument. - flag player my_flag:"my value" is entirely invalid and considered an error.

Also, you should not put quotes around an argument that does not contain a space. For example, - flag "player" "flag:value" is full of redundant pointless quotes.

You should also never use quotes around a command name, or script key. In the following example, every single quote is bad and should be removed.

"This is wrong":

"type": "task"

"script":

- "flag" player flag:value

Here's how that should look:

This is right:

type: task

script:

- flag player flag:value

Watch Your Debug Console

When you're writing scripts, you should always have your server debug console open and ready. When you run a script, keep that console in your corner of your eye and look over it when applicable. If an error message appears in your console, that will both tell you that you need to fix something, and tell you what you need to fix far faster than trying to review your script to find what you might have screwed up.

When users come to the support Discord to ask for help with a problem, we usually ask for a debug recording. Far too often, they'll post a debug recording with a bright red visible error message that says exactly what went wrong. Had the user simply been watching their debug console and saw the error message, they could have resolved the issue quickly on their own, without having to ask for help.

Debug output also shows a lot of non-error information, which tends to be very useful when working on a script. Your custom-drops script is dropping too many items - why is that? The debug logs will show you a repeat loop going too long, or a quantity value being set different than you expected, or whatever else happened. You're not sure what that event context of an enum value might be when the event fires... the debug logs will show you what it is!

Toggle Debug Settings With Care

First of all: NEVER disable the global debug output. Debug information is extremely important to have. A global disable will hide everything, even error messages! Instead, simply set debug: false on scripts you want to stop showing debug output.

Here's where you fit a debug: false onto a script:

No debug script:

type: task

debug: false

script:

- define a b

- (commands here)

It should always be right after the type: line, at the same level of indentation.

When debug: false is set, the only debug information from that script that will show will be error messages. When it is not set, all debug information will show.

As a general rule of thumb:

When you are editing a script / working on it, in any way, you should never have debug disabled.

When you are FULLY DONE with a script, it works, it's tested, you're happy with it - THEN you can disable debug on it.

Live Servers Are Not Test Servers

When helping people on our Discord, we sometimes hear things like "I can't restart the server right now, players are on" or "oh woops a player accidentally triggered the event".

If you have a LIVE server, with ACTUAL PLAYERS online, you should NOT be writing scripts on it. ALWAYS set up a local test server for script writing, and move the scripts to the live server later, after the script fully works.

It's simply too easy to cause a lot of problems for a lot of people when you're editing a live server. Don't do it.

If True Is True Equal To Truly True Is The Truth

The way the if command in Denizen works is it processes the arguments using logical comparison techniques, then runs the code inside if the result is true, and does not if the result is anything else.

So, if a script does - if <sometag> == true:, you're essentially saying if ( true == true ) == true: ... which is pretty silly, right?

NEVER input == true into an if command (or while or anything like it). It is always redundant.

Also, do not input == false. Instead, to negate a check, use !. So for example, - if !<some tag>: or - if <some tag> != somevalue:.

Text Isn't A Tag

Users who are new to Denizen often misread documentation like <#> in a command syntax as meaning that <3> is valid input.

This is not correct, as the command syntax explanation writeup explains, in that context the <> means "insert a value here". The <> are not meant to be literally included.

So, if a command says its syntax is - heal [<#>], correct input might look like - heal 3.

A key reason for this confusion stems from the fact that <> is often actually used in Denizen scripts to form a tag. The thing to remember is that tags are never literal - they are an instruction to the script engine to go find some other value. The tag <player.money> for example does not mean to insert the plain text "player.money" into a command, it means to find the amount of money the player has, and put that value in. So, - heal <player.money> in a script would process the tag's value and end up processing the command like - heal 3 (if the player happened to have $3 at the time).

If at any time you want to insert literal text: just insert literal text, will nothing more to it. - heal 3 or - narrate mytexthere are perfectly valid ways to write arguments, with no need for any special symbols (except when quotes are required to contain a space within an argument).

As an additional note, if you need literal text in the form of a tag (to use some element sub-tag on it), you can use the element base tag, like: <element[3].div[5]> (this takes the plain value "3", forms it into an ElementTag, then uses the ElementTag.div sub-tag to divide it by 5).

The Adjust Command Is Not For Items/Materials/Etc.

Many users, when first trying to adjust a mechanism on an item, material, or similar type, will try to use the adjust command to achieve this, like - adjust <[inventory].slot[5]> "lore:My new lore!" or - adjust <[location].material> lit:true.

While this does seem to make sense initially, it unfortunately will not work out, due to an important distinction between object types: unique vs. generic objects. It is recommended that you read and understand that explanation page to properly understand why you cannot adjust an item, but the short summary is: ItemTags look like stick, which is a description of an item, not a single unique item. As a result, the system has no way to track down which stick you're trying to adjust.

If you do use adjust on an item, it will apply the modification to the description of the item, and store the modified description into a save entry. A similar result happens with a MaterialTag object. While this may be useful in some cases, this isn't useful when you want to change an actual specific item in the world.

So, How Do I Adjust A Specific Item?

The way to properly adjust a specific item changes depending on where that item is. If the item is inside an inventory, the best way is to use the inventory command with the adjust and slot:<#> arguments (like - inventory adjust slot:5 "lore:My new lore!"). In other cases, the tag ItemTag.with[...] is useful. This tag returns a copy of an item with a mechanism applied. So if, for example, you have a dropped_item entity, you can adjust the item mechanism on that entity to be the result of a with tag, like: - adjust <[entity]> "item:<[entity].item.with[lore=my new lore!]>". To change the item in an event, you might also be able to use determine with the ItemTag.with tag.

To adjust a MaterialTag, there is a MaterialTag.with[...] tag that matches the ItemTag version. Most likely, however, you want to adjust the material of a block, so the adjustblock command is what you need. It takes the location of a block, and applies MaterialTag mechanisms to that specific block (like - adjustblock <[location]> lit:true).

The same logic applies to flagging items - don't use the flag command, use inventory flag (like - inventory flag slot:5 myflag:value) or the with_flag tag.

Don't Script Raw Locations

On the Denizen Discord, we often get questions like "how do I put in the coordinates for a location" or "how do I make the NPC walk to x,y,z 1,5,7" or something like that. Sometimes it even gets phrased like "how do I give raw coordinate values instead of using a LocationTag".

The short answer: You don't do that.

As a general matter of clean and proper scripting, it never makes sense to type world coordinate values directly into a script instead of using a tag to get the location.

But What If There Isn't A Tag For The Location I Want?

Then make one! Denizen tags are not unmovable boulders. They are tools, and they work for you, not against you.

If, for example, you have a fancy pillar of obsidian at the center of your arena build, and you need scripts to use the location of the pillar... simply stand on top of the pillar, and type /ex note <player.location.below> as:arena1_pillar. Now that you've done that, any script that needs the location can literally type in arena1_pillar as a location. Need an NPC to look at the pillar? - look arena1_pillar. Need to get the exact Y height value of the pillar? <location[arena1_pillar].y>. Clean, descriptive, and easy!

If, for example, you have an NPC that needs to walk towards specific points on a path, you might at that point use anchors. Select the NPC, then stand at each point on the path and type /npc anchor --save point1 (then point2, then 3, etc). Then, the script can do - ~walk <npc.anchor[point1]> (and then point2, 3, etc).

If you need a location that changes from time to time, or is selected from a list of possibilities, or is attached to a player instead of an NPC, or... you might in that case store the location into a flag.

Don't Type Raw Object Notation

Denizen uses object notation internally to track object types. For example, l@ indicates a value is a location, p@ indicates a player, etc.

This is exclusively intended for internal tracking of generated values. A script should NEVER contain these object notation values typed out.

Instead of typing the object notation out, use one of these three options:

Just leave it off. Often, you can input a value without in any way specifying the type, and it will just work (refer to Don't Overuse Constructor Tags for related information).

Use a tag that returns a relevant value, rather than trying to specify a raw value in the first place (refer to Don't Script Raw Locations for related information).

Use a constructor tag when needed (refer to Don't Overuse Constructor Tags for related information).

Object Hacking Is A Bad Idea

Denizen has standard formats for most object types. For example, ItemTags look like i@stick[lore=Fancy stick].

These formats are used for internal tracking purposes, and should be kept that way. They are generated internal values, not meant to be manipulated via scripts.

We sometimes see users try things like <player.item_in_hand>[lore=Fancy stick]. This example, if the player is holding a stick, will create a new item that is a stick with that lore, just like the user wanted. However, if the player's held item already has any additional data on it, it will end up processing into something more like i@stick[display_name=Best stick][lore=Fancy stick], and that no longer matches the standard format, and thus will not work. (The correct non-object-hacking way, for reference, to get a copy of an item with additional mechanisms, would be <player.item_in_hand.with[lore=Fancy stick]>).

Something to bear in mind as well is that standard formats change as the underlying object needs to hold different forms of internal data. For example, MaterialTag was originally formed like m@chest or m@chest,2, but now has a format more like m@chest[direction=north]. While old data that was stored using an older format will generally still be parsed in correctly (at least for a period of time after the initial change), any scripts expecting the format to be a certain way will instantly stop working.

The most common recent example of object hacking biting people in recent times is ListTag object hacking. The original ListTag format was li@one|two|three, which still works perfectly fine as input, but no longer is the standard output format. Several users had scripts with lines akin to <some_list>|additional|value|here which worked with the old format. However, the format was changed to allow for things like sub-lists via built-in escaping logic, and distinguished itself with an additional | on the end. This format change also allowed for empty entries to exist in ListTags. This resulted in those object-hacking scripts having escaped data in the list, but looking like old-list-format to the parser, and thus not having the escaping parsed, and thus suddenly the hacked lists had corrupted data. (The correct non-object-hacking way, for reference, to add entries to a list is <some_list.include[additional|value|here]>).

The lesson here is: never assume that the full object format for an object is going to be a certain way. There's always a tag to read or change any data within an object in a better way.

Creative Gamemode Inventories Are Clientside

Many server admins tend to leave themselves in creative mode while working and even while testing things meant for survival-mode players to interact with. While this usually works out fine, there are some cases where the differences between gamemodes can bite you. Some are obvious (for example, you can't test a script that damages you if you can't take damage), some aren't obvious at all. The non-obvious case that most often confuses scripters is inventories.

Normally, in gamemode survival (or adventure), inventories are serverside. This means that the server has the final say on which items are where, and further means that any serverside scripts or plugins can modify and control any inventory or interaction with an inventory, and trust that it will work.

However, while in gamemode creative, inventories are clientside. This means that the client (the code running on the player's own PC, whether it's a vanilla minecraft client or a modded one) has final say on the details of an inventory. While servers can still make their own changes to inventories or interactions, the client can overrule those changes. This leads to things like trying to cancel a click event duplicating the item (the server said "no, A: you don't pick up the item, and B: that item is still in its original slot" ... the client decides "I deny A, I did in fact pick up the item, it's mine now, but I'm okay with B, that item can still be in its original slot" ie there's now two copies of the same item).

A related part of this system that is worth thinking about, is that players in creative gamemode have the ability to spawn any item they want. On a vanilla minecraft client, that means they can either A: grab any new core item or stack of items from the creative item list at any time, or B: produce a perfect copy of any item they see by way of middle-clicking on that item (this might for example be used to get a GUI-only special scripted item into their own inventory). A modded client, however, could potentially spawn any item, even ones with custom NBT data on them. This is worth thinking about any time you link some power or system to data on an item. Consider the following script:

dangerous_powertools:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks block with:powertool_item:

- execute as_server <player.item_in_hand.flag[powertool_command]>

powertool_item:

type: item

material: stick

flags:

powertool_command: broadcast It Works!

At first glance, this script enables the creation of simple 'powertool' items that execute custom commands... however, because 'as_server' is used with per-item data, that means a creative player could generate an item with any command and bypass any permission requirements (an ill-intentioned creative-mode player might make use of this to op themselves, or ban the server owner, or...).

The Ex Command Is For Testing Only

Some users have tried using /ex as a general purpose scripting tool - but that's not quite right. It is designed to be used for testing/debugging only.

In other words: the only place /ex should ever appear is in your in-game chat bar. It should never be placed into a script, into a command block, into another plugin's command, etc.

One of the most common ways /ex gets misused, is getting placed inside some other plugin's configuration as a triggerable command, such as a shop plugin that is configured to trigger /ex run mytaskname player:%player% when an item is bought. This is a bad way of going about things - it's firing up the full parsing engine and preparing debug output and all that, every single time a player triggers that option. What should you do instead? Simple: make a command script! Have the command script do whatever is needed, and then add the command name into that external plugin as the command to trigger. (Or, of course, you can also just replace the external plugin entirely with a Denizen script, if you're up for it!)