Changing The Path: The If Command

What Is The 'If' Command?

You learned how to use events to run a set of commands whenever a situation occurs on your server. You learned how to use tags to change what any command does based on the details of the situation.

Now it's time to use the if command to combine the two concepts: choosing a set of commands to run based on the details of the situation.

The if command does exactly what it says on the tin: it says "if something is true, then run these commands. Otherwise, don't run them."

So What Does An If Command Look Like?

Don't worry, if commands are pretty easy to write, and look just like anything else in a Denizen script does.

Here's the basic format:

- if (some condition here):

- (some commands)

- (go here)

As you can see, if is a command (written just like any other at the start, with some condition(s) as its input arguments)

but with a : on the end (just like you would have on an event line),

and some commands spaced out and placed within. The thing to be extra careful about here is the spacing on the commands within.

If the commands within don't get spaced out a step, Denizen won't know that they were meant to be in the if, and just run them regardless of the condition you give.

Let's see how this might look in a real script...

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

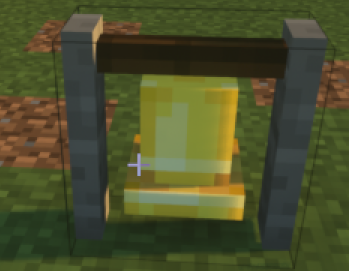

- if <player.health_percentage> < 25:

- heal

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

This handy sample script will instantly heal a player that clicks on a bell block, but only if their health is dangerously low. (We'll expand on this sample script throughout this section, and when we get to the Flags section we'll revisit this sample script to add a rate limit, so players can only heal once every few minutes).

This script also displays an actionbar message to let the player know they've been healed, using the base text color defined in your Denizen config.yml file.

Conditions

There's a few different ways to make a condition in an if command.

At its simplest, the condition could be a boolean tag (one that returns 'true' or 'false'), and that's enough right there. (For example, - if <player.on_fire>:).

The if sub-commands will run when the tag returns true, and won't when it returns false.

You can also invert (run when the tag is 'false', and don't run when it's 'true') these simple boolean if commands using the ! symbol (which is read as "not").

For example, - if !<player.on_fire>: will run only if the player is not on fire.

It could also be some value tag (a tag that returns anything more complicated than a boolean), in which case it will be compared to some other value.

The basic format of an if command that compares two values is - if (first value) (comparison) (second value): (for example, - if <player.name> == mcmonkey4eva:).

One or both values can be a tag. (Technically, both values can also be static text, but that would mean the if command either always runs its sub-commands, or never does... that's not a very useful if command).

There are a few different comparison types available:

==to test equality (- if 3 == 3:will run its commands, but- if 3 == 4:will not) - you can read this as "if three is equal to three, then run some commands".

!=to test equality but expect the opposite result (so,- if 3 != 3:will not run its commands, and- if 3 != 4:will run its commands) - the!is read as "not", so you can read this like "if three is not equal to three, then run some commands." Of course in real usage, one or both of the values would be from a tag.

>(is greater than),>=(is greater than or equal to),<(is less than), and<=(is less than or equal to) to test numeric comparisons. Note that>and<=are opposites, and that<and>=are opposites. As a special additional note here: you might notice that<and>are the symbols used to indicate a tag normally, but are used for a different meaning here - this is fine, as you will never have both<and>in a single argument of a comparison, and thus the symbols will never be misinterpreted as a tag.

containsandinfor list containment checks, like- if one|two contains one:or- if one in one|two:

matchesfor advanced-matcher checks, like- if <player.item_in_hand> matches diamond_sword:

Combining Conditions: The Venti Mocha Frap With Extra Sugar and No Cream

When a simple comparison just won't do, and you gotta get a few extra things included, don't worry: the if command will let you do that!

There are two combination types available:

If you want a set of commands to run if multiple comparisons are all true, use

&&(read as "and" - the symbol itself is a double-ampersand). For example,- if <player.on_fire> && <player.health_percentage> < 25:will run its commands if a player is on fire and almost dead.

If you want a set of commands to run if any one (or more) of multiple comparisons is true, use

||(read as "or" - the symbol itself is a double-pipe). For example,- if <player.on_fire> || <player.health_percentage> < 25:will run its commands if a player is on fire (regardless of their health), or will run its commands if the player's health is low (regardless of whether they're on fire).

If you have a lot of things you want to specify at once, you can simply chain these together in a row: - if (condition one) && (condition two) && (condition three) && (condition four):.

There's only one complication: chaining together only ones if you have && all the way down the chain, or you have || all the way down the chain.

You can't have both in one chain... think about it, - if (one) && (two) || (three) && (four): ... what does that mean?

Does that mean we must either have one and two, OR have three and four? It could also mean we must have one, two or three, and four.

We as humans might be able to make a good guess as to which was intended, but Denizen is just software, it can't read minds.

The solution to this problem was hidden in the way I asked the question: if you look at the way I specified the two possible interpretations, you'll notice I carefully grouped parts together, and separated the other parts into a list.

Denizen contains a syntax to do the very same: parentheses () with extra spaces can be used to mark groupings.

So how do we use that?

Here's a long but relatively simple example:

- if ( <player.name> == mcmonkey4eva && <player.health_percentage> > 90 ) || ( <player.on_fire> && <player.health_percentage> < 25 ):

- narrate "wow mcmonkey specifically is doing pretty well! That or somebody is dying from a fire..."

Using grouping as shown above, you can make any combination of conditions you might ever need. You can even put groups inside of other groups if you really want to, but be aware that going too crazy can make your script hard to read, and a better organization might be preferable (see next sub-section below for one good alternative).

The Most Common Usage of 'If'

The benefit of the if command in the 'magic healing bell' example earlier is pretty straight forward: it allowed us to narrow down exactly when a set of commands should run.

Rather than just "whenever a player clicks a bell", it's now "whenever a player clicks a bell, and that player has low health".

Narrowing down the requirements for commands to run is, generally speaking, the most common usage of an if command.

You will very often see this in real scripts in a slightly different form, but accomplishing the same goal:

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

- if <player.health_percentage> > 25:

- stop

- heal

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

By using the stop command inside an if, we are able to stop the script from running the heal command if a player's health is greater than 25%.

This is functionally the same as the original script, but expressed 'backwards'

(instead of "if the player has below 25% health, heal them" we instead say "if the player has above 25% health, they don't get healed").

This is very useful when you have multiple things you want to require before you want the actual script commands to be ran, as they can expressed neatly in order

(rather than getting stuck with a very long line listing all your conditions).

A Fork In The Road

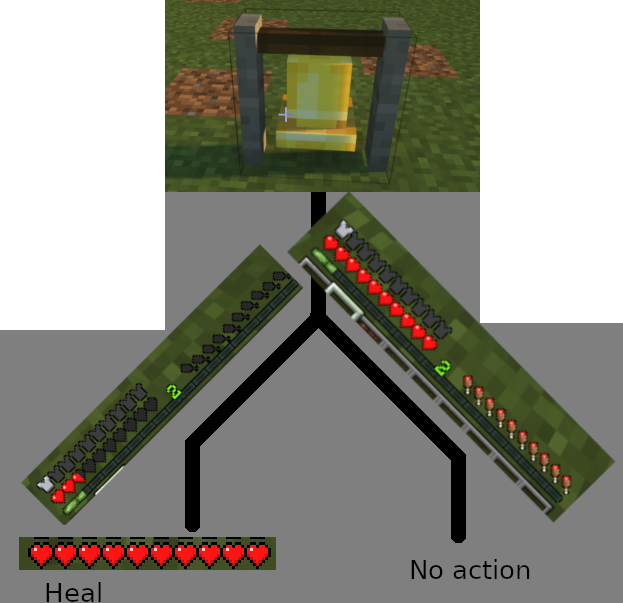

So far, we've explained the basics of the if command in terms of how to run a set of commands or not run them, based on some condition.

This is great for adding extra requirements to an event before a set of commands runs, but that's not all that if can do!

The if command, as we currently understand it, says "if this condition is true, then run these commands, otherwise don't."

Let's expand that to instead say "if this condition is true, then run these commands, otherwise run these different commands."

Now, our script can go down one of two paths depending on some tag-based condition.

We'll do this using the else command.

What Does An Else Command Look Like?

The else command looks almost the same as an if.

Here's the basic format:

- if (some condition here):

- (commands for when the condition is 'true')

- else:

- (commands for 'false')

That's pretty simple! It's just an else with no input parameters, formatted just like an if, and with the special requirement that it must be right after an if.

Whenever the if command's condition is 'false', the commands in else will run.

Let's make use of an else in our magic bell script...

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

- if <player.health_percentage> < 25:

- heal

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

- else:

- actionbar "<&[error]>The bell does nothing: you're healthy enough already."

The existing script healed players with less than 25% health. Now it will also give a message to players that are healthy enough, so they don't get confused when the bell doesn't do anything.

You might ask "well, why don't I just use the stop command the way you showed earlier, and put the rejection message right before the stop command?" - And you can do that!

That's a great way to do that. So what good is the else command? It's much more useful when you have things that go after the if/else commands, that need to run regardless of what happens with the if/else.

Consider this script:

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

- if <player.health_percentage> > 90:

- actionbar "<&[error]>The bell does nothing: you're healthy enough already."

- stop

- if <player.health_percentage> < 25:

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has saved you!"

- else:

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

- heal

This script will reject the player if they have at least 90% health, and heal for anything below that.

It gives a unique message depending on whether the player is almost dead, or just a bit low.

If we didn't use an else command here, we would have had to do this:

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

- if <player.health_percentage> > 90:

- actionbar "<&[error]>The bell does nothing: you're healthy enough already."

- stop

- if <player.health_percentage> < 25:

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has saved you!"

- heal

- stop

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

- heal

That's a lot worse! We had to write the heal command twice (not to mention the extra stop command).

If you're thinking "that's not too bad", just think about how much worse that might get in a real script where there's a lot more than just a single heal command that runs regardless of the condition.

You'd be duplicating an entire list of commands - luckily, the else command lets us avoid that!

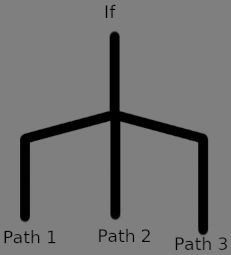

Don't Forks Normally Have 3 or 4 Prongs?

The else command is pretty handy as we've seen, but it actually has even more power to it!

We started out with just an if command that lets you make one subset of code run or not run.

We then expanded to the else command to let you run one of two possible subsets of code.

You can probably guess what we're expanding to next: a way to choose one of many possible subsets of code.

This is the else if!

How Do You Write An 'Else If'?

Here's the basic format:

- if (first condition here):

- (commands for when the first condition is 'true')

- else if (second condition):

- (second condition 'true' commands)

- else:

- (commands for when all conditions were 'false')

As you can see, it's pretty much just slapping an if inside of an else.

You can chain else ifs in a row as many times as like, the only limit is you must always start with a regular if.

You do not have to have an else (without the if) but you can if you want, it just has to be kept at the very end if so.

How might that go in real usage?

magic_healing_bell:

type: world

events:

after player right clicks bell:

- if <player.health_percentage> > 90:

- actionbar "<&[error]>The bell does nothing: you're healthy enough already."

- else if <player.health_percentage> < 25:

- actionbar "<&[error]>The bell can't save you: you're too far gone."

- else:

- actionbar "<&[base]>The bell has healed you!"

- heal

This version of the magic bell script won't heal you if you're healthy already, and also won't save you from death - it will only heal you if you're moderately injured.

Thanks to this new design, we don't need the stop command at all anymore, as the heal command only runs on one of the possible "branches".

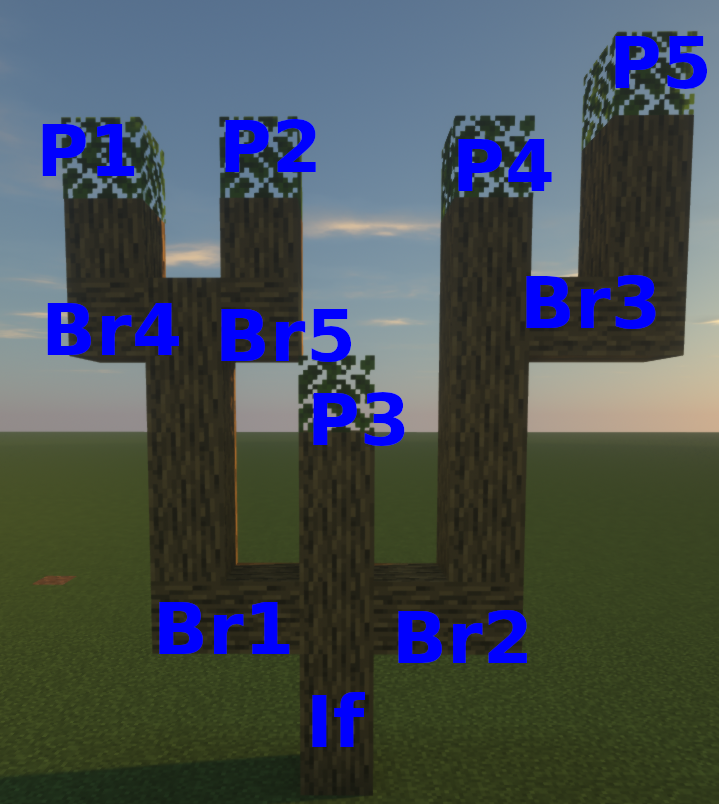

Wait Who Was Talking About Trees?

If you have experience in advanced computer processing design - well, first of all, why are you bothering to read this guide? but more relevantly - you might recognize the term "branch" being used here. If not, you might still recognize the idea of visualizing paths as trees with many branches. If you don't have any idea what I'm on about, don't worry, I'll explain.

The different ways an if command might go are sometimes called "branches", usually when using this terminology the overall structure of a script is called a "tree".

When a script is being ran, it starts at the "root" (whatever the first command is),

and it "branches out" any time you have an if command or similar (any subset of commands that only sometimes runs).

You don't have to know or use any of these terms or any others like it we introduce, but if you see someone using them and don't know what they're talking about, hopefully you'll remember that this subsection exists to come look back at!

Another common phrasing you might want to be aware of is "pass" and "fail" - an if command "passes" when its conditions are true (and its sub-commands run).

The if has "failed" when its conditions are false (and its sub-commands don't run).

Going Beyond

If you're sitting here thinking "well this is all well and good, but there's so many more complicated ways I want to branch my scripts",

well... you've reached the end of the general overview of the if command here. Depending on what you want to do,

you might just go ahead and stick an if command inside of another if command (nothing's going to stop you, other than than your script starting to look big and scary),

or if that's not good enough... well keep reading through the guide, one of the upcoming sections will probably have what you're looking for (like the Loops section).